National Famine Commemoration at Strokestown and the Irish Famine Migration to Canada

The annual famine commemoration took place in Strokestown, County Roscommon on Sunday May 11.

Irish leader Enda Kenny, who was present, stated, “In remembering our past, we must not lose sight of our present.

“Our history of famine means that Irish people have a particular empathy with those suffering the effects of hunger in the world today.

“As Taoiseach, in honor of our Famine dead, I’m proud to be able to say that combating global hunger and undernutrition is central both to Ireland’s foreign policy and to our overseas development-assistance programme – Irish Aid.”

Strokestown now houses the famine museum. In 1847, 5,000 Irish left Co Roscommon on four ships bound for Canada. Fewer than 1500 people survived, but until this year, the destiny of those “missing 1490” remained unknown.

A project by the University of Maynooth has uncovered the fate of a large number of the survivors. A memorial wall was unveiled this weekend containing the names of the emigrants.

Dr Ciarán Reilly of the Centre for the Study of Historic Irish Houses and Estates, NUI Maynooth in conjunction with Strokestown Park House, led the research.

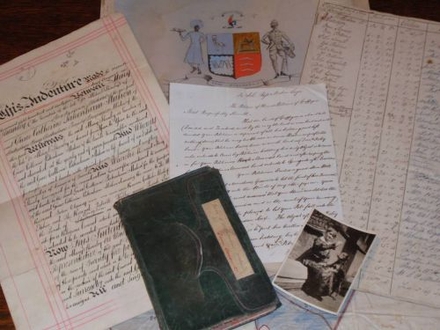

He found much of the information for the project from the Strokestown archive, which houses more than 50,000 documents, the majority related to the Great Famine.

The people were mass evicted from the Strokestown estate in Co Roscommon after Major Denis Mahon inherited the 11,000 acre estate following the murder of Rev Maurice Mahon, third baron Hartland in November 1845.

After years of neglect and mismanagement, the estate was nearly £30,000 in debt and suffering from gross overcrowding.

John Ross Mahon, the land agent, came up with the scheme of assisted emigration after discovering that it would cost over £11,000 annually to keep the people in the Roscommon workhouse but only £5,800 to help them emigrate.

“In May, 1847 1,490 tenants left from the Strokestown estate for Quebec in British North America (Canada). They were accompanied on their walk to Dublin, by the Royal Canal footway, by the bailiff, John Robinson who was instructed to stay with them all the way to Liverpool and ensure that they boarded the ships,” Dr Reilly told TheJournal.ie.

They left on four ships: the Virginius, Naomi, John Munn and the Erin’s Queen.

“The Mahon tenants were amongst the first to be characterized as sailing on coffin ships during the Famine,” said Reilly. “With Cholera and typhus rampant the emigrants were exposed to the ravages of disease.”

The journey took the lives of many of passengers and the majority of those who lived became sick.

Reilly says the survivors were described as “ghastly, yellow-looking spectres, unshaven and hollow cheeked.”

To trace the lives of those who survived the arduous trip, Dr Reilly searched census records, the Strokestown newspapers archive, obituaries, and many online archives, including the Library of Congress.

He found many of the Strokestown emigrants were interviewed by Canadian papers once they landed. Reilly told TheJournal.ie that obituaries were also helpful, as the Irish communities in various countries tended to post “a lot of fairly informative obituaries” that often included the names of famine ships.

Several of the immigrants, such as Michaell Flynn, James Higgins and Thomas Fallon, fought in the American Civil War. Patrick McNamara was a laborer on the construction of the Blue Ridge Mountain Railroad Tunnel.

Mary Tarpey, who lived to be 106, had the distinction of being the oldest person in Long Island at one point. “She attributed her longevity to a daily glass of whiskey,” said Reilly.

The famine and the long and harsh conditions of the journey to the United States also took a mental toll on many people.

“The ones that don’t adapt and don’t make it in America, you would find them in asylums,” said Reilly.

“I found several in mental asylums within a year or two of reaching America. It’s obvious they have left scarred and totally can’t adapt. Others you find in almshouses.”

Dr Reilly will publish his findings this fall in “Voices of the Great Irish Famine: The Strokestown Archive Revealed.”

The Taoiseach Enda Kenny attended the commemoration with the Minister for Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht Jimmy Deenihan. Kenny unveiled the memorial wall at Strokestown Park listing the names of the formerly “missing 1,490.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u6htdrHAFBI

Read more: http://www.irishcentral.com/roots/history/Irelands-annual-Famine-commemoration-takes-place-in-Roscommon.html#ixzz31cOyHfEn

Follow us: @IrishCentral on Twitter | IrishCentral on Facebook

is

is